Some 30 centuries ago someone in China was developing, a sort of mouth organ called a sheng, and came up with the idea of the free reed. (A copy of the Sheng can be found in the accordion museum of Castelfidardo in Italy.) In Europe in the early 1800's, as the Romantic revolution is gathering momentum, there is a search for new musical instruments. The inventors of the day are very much interested in the free reed. Research on its use is carried on in St. Petersburg by a physicist named Kratzenstein, the inventor of an automa-ton that can simulate human vowel sounds. It is said that he showed a sheng to an organ maker named Kirschnik, who found a way to incorporate the free reed in his instruments.

Some 30 centuries ago someone in China was developing, a sort of mouth organ called a sheng, and came up with the idea of the free reed. (A copy of the Sheng can be found in the accordion museum of Castelfidardo in Italy.) In Europe in the early 1800's, as the Romantic revolution is gathering momentum, there is a search for new musical instruments. The inventors of the day are very much interested in the free reed. Research on its use is carried on in St. Petersburg by a physicist named Kratzenstein, the inventor of an automa-ton that can simulate human vowel sounds. It is said that he showed a sheng to an organ maker named Kirschnik, who found a way to incorporate the free reed in his instruments.

I've always thought that certain ideas seem to be "in the air," so that an invention will be claimed by almost simultaneous discoverers. That was the case for the organ, the harmonica and the accordion. There is certainly a similarity between the sheng and the harmonica, the latter instrument playing a major or role in the development of the accordion.

The tiny mouth organ is invented in 1821 by a German adolescent named Christian Friedrich Buschmann, who names it the aura. It contains some 15 reeds and slots into which a musician can blow to make the reeds vibrate. It looks like a toy at first glance. The same year, two German clockmakers work to improve it, and subsequently a Bohemian violin maker, Paddy Richter, adds aspired notes, allowing the instrument to sound two different notes per slot, tuning it diatonically to what will become known as Richter tuning. The extraordinary sounds the instruments can produce make it a phenomenal success, and its popularity spreads far and wide. It becomes the link between the older family of reed instruments and the accordion.

There are, however, two sides to a coin. You can't play the harmonica and sing at the same time. Simultaneously, then, several inventors search for ways of making a portable instrument that allows a singer to accompany himself. The new instrument must be melodic, polyphonic and expressive, capable of adding panache to any festivities. In 1829, only a month apart, two inventors file for a patent.

The first is filed by an Austrian of Armenian descent, Cyrille Demian, who along with his two sons is an organ and piano maker. His Akkordion is a small box inside which there is a series of metal reeds and a bellows. Its five keys can produce two chords each, whence the name, depending on whether the bellows is pushed in or drawn out (this diatonic, "two tone" system is sometimes called bisonic). The new instrument is light and mobile, and easy to play. In an age before radio and TV, when singing and reciting are common pastimes, the new instrument is a boon to music lovers. It will quickly evolve into the familiar diatonic accordion of today. Manufactured in Austria, France and Italy from 1860 onward it will spread across the world.

The first is filed by an Austrian of Armenian descent, Cyrille Demian, who along with his two sons is an organ and piano maker. His Akkordion is a small box inside which there is a series of metal reeds and a bellows. Its five keys can produce two chords each, whence the name, depending on whether the bellows is pushed in or drawn out (this diatonic, "two tone" system is sometimes called bisonic). The new instrument is light and mobile, and easy to play. In an age before radio and TV, when singing and reciting are common pastimes, the new instrument is a boon to music lovers. It will quickly evolve into the familiar diatonic accordion of today. Manufactured in Austria, France and Italy from 1860 onward it will spread across the world.

A little more than a month after Demian's patent filing, an English physicist, Charles Wheatstone, files his own patent request for his symphonium, a bellows-driven instrument which becomes the concertina (not to be confused with the German Konzertina of 1856, ancestor of the Bandonion of tango fame.) Wheatstone's concertina has a hexagonal shape and has two independent keyboards but no predetermined chords.

Each note sounds the same whether the bellows is drawn or compressed. This precursor of the concert accordion draws a great deal of interest, including that of no less a luminary than Hector Berlioz.

At first it is Demian's Akkordion that becomes popular, in an age when — in music as in literature and art — emotional effect is deemed more important than performance details. Brought to France by imigrants, Demian's instrument is quickly adopted by the French, some of whom dismantle it to see how it works. Seeking the advice of musicians, they rework its innards. Two years after its initial invention, there is a French accordion method named after Pichenot, who equips his instrument with a valve switch to evacuate air from the bellows. In Paris and all around France, accordion classes are organized, and the most daring musicians play even Mozart and Rossini, arranging their music to suit the possibilities of the little instrument.

Painters and craftsmen collaborated with each other to add visual embellishments to this romantic instrument, using inlaid wood and ivory, keys of sculpted mother of pearl, and colorful bellows, all decorated with pearls and spangles. The instrument becomes a work of art in its own right. In its formal wear, it is welcomed into the salons of the nobility and the haute bourgeoisie, especially once King Louis-Philippe acquires one for himself. In Paris society it is à la mode to own one.

In 1832 in Paris, professor and accordion maker A. Reimer opens a workshop dedicated to the development of Demian's invention. He adds a melodic keyboard, in which each key produces just one sound. His romantic accordion can be heard in the salons of the highest society. The very first accordion concert takes place on April 10, 1836 at Paris City Hall. Reisner's daughter Louise introduces the accordion to the world of "serious" music, playing her own "Thème varié très brilliant"

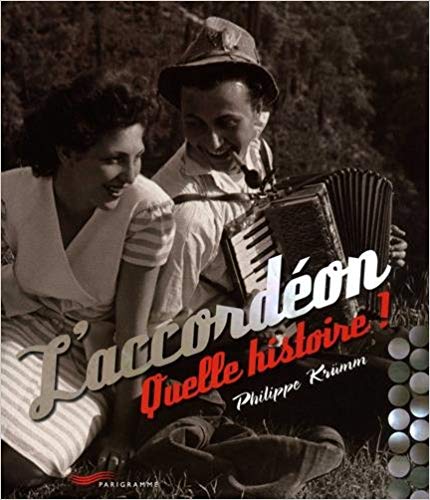

Without truly leaving the world of Parisian salons, the accordion spreads to the countryside, becoming immensely popular at country dances, bistros, weddings and even Church holidays. It is everywhere. It is affordable and easy to learn, with one hand playing the melody and the other supplying complete chords. It will become an important folk instrument around the world.

Ironically it is its very ease of play that will long keep it out of music schools and conservatories. It will ultimately triumph over the reticence of "serious" musicians, thanks to continued development by both musicians and accordion makers. French accordion maker Leon Doucet patents his accordéon harmonieux, ancestor of the chromatic accordion. Equipped with two bellows, it can sound the same note whether the bellows are drawn or compressed. French accordion making is underway.

Other innovations are to come. In 1850, F. Walter places two identical reeds in the same voice, an idea picked up 47 years later by Soprani. In 1852 Matthaus Bauer builds the first accordion with a piano keyboard for the melody. On the left side, buttons are still used to play chords.

In 1898, in Roubaix, France, the Fanfare des accordéonistes roubaisiens is created. Incorporated by the local prefect two years later, it is the envy of other towns, which hasten to form similar bands. The enthusiasm of ordinary people for the accordion is formidable. Yet even if Tchaikovsky incorporates an accordion in his Suite No. 2 in C Major; the music academies remain cool.

In 1898, in Roubaix, France, the Fanfare des accordéonistes roubaisiens is created. Incorporated by the local prefect two years later, it is the envy of other towns, which hasten to form similar bands. The enthusiasm of ordinary people for the accordion is formidable. Yet even if Tchaikovsky incorporates an accordion in his Suite No. 2 in C Major; the music academies remain cool.